There was nothing funny about the way Jeff Lawson left Twilio, the startup he cofounded in 2008 and built into a multibillion-dollar public company enabling businesses to communicate with customers via text messages and phone calls. Activist investors had been pushing for management changes and even a sell-off, and Lawson resigned from his CEO post in January. He now describes his role at Twilio as “shareholder.” No wonder he needs a good laugh.

Since he’s a rich person, Lawson has the means to acquire all the chuckles he could ever need, with some belly laughs thrown in. Last week he bought the legendary, though somewhat faded, satire factory The Onion. To do so, he set up a company called Global Tetrahedron, inspired by the name of an evil fictional corporation used as a running gag by Onion writers.

Lawson won’t say what he paid. To operate the site, he hired former NBC reporter Ben Collins as CEO, former Bumble and TikTok executive Leila Brillson as chief marketing officer, and Tumblr’s former director of product Danielle Strle as chief product officer. He promised to retain the entire editorial staff. Then he immediately did something that was never part of the Twilio business model. He asked The Onion’s customers to give their money to him—in return for “absolutely nothing,” says Lawson. Suggested donation: one dollar.

Remember when The Onion was a huge cultural force? It was founded in 1988 in Madison, Wisconsin—even now it’s in Chicago, cleverly avoiding both smug coasts—and rose to a beloved status, first in newsprint and then online. Everybody seemed to read it, and quote it. Some of its memes still resonate—the headline “‘No Way to Prevent This,’ Says Only Nation Where This Regularly Happens” gets republished after mass shootings, over 20 times so far, and never fails to draw attention. But it’s been a long time since its 1999 book Our Dumb Century was a runaway bestseller. There was even an Onion movie, though it was no Animal House; five years after it was shot, it was released direct to video. In recent years, Lawson says, even though The Onion’s loyal writing crew remained mordant and witty, visiting the site was not much fun. As Lawson wrote in a tweet, under the traffic-obsessed regime of its owner G/O enterprises “The Onion has been stifled, along with most of the internet, by byzantine cookie dialogs, paywalls, bizarro belly fat ads, and clickbait content.”

How will Global Tetrahedron fix that? “The vision is to basically unshackle The Onion from this very traffic-driven strategy of pageviews and programmatic ad impressions,” says Brillson. “We want to get out of their way and make them a truly independent space, as opposed to being a part of a private equity venture.”

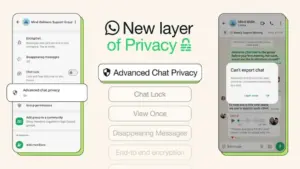

That’s where the dollar donation idea comes in. When I told Lawson it reminded me of the original dollar-per-year fee charged by WhatsApp in the years before Facebook purchased the service for $22 billion, he confirmed that was indeed the inspiration. WhatsApp had been a Twilio customer, and Lawson at first didn’t understand the point of the fee. One day he asked WhatsApp cofounder Jan Koum about it. It was sometime around 2010, and there were new chat apps popping up every day. “I asked Jan, ‘Why are you charging $1—with all those competitors, why would you put this friction in your signup process?’” Lawson recalls

Koum replied that the fee was critical because chat apps were a dime a dozen. “Usually, you just download a chat app, use it for five minutes, and you delete it,” Lawson recalls Koum explaining. “But if you ask someone to put up $1, and they do, they have a financial investment in it. It’s a symbolic thing. Once you put something in, you care about it more.” Not to mention when hundreds of millions of people signed onto the service, those dollars turned into real money.

So as soon as Lawson closed The Onion deal, he asked to set up something where people could chip in. “We absolutely do not envision a hard paywall, but we wanted to say that if this is a publication that made you laugh, and one you love, get used to the idea that maybe you’re going to pay something,” he says. The Onion writers took it from there: “Give Us $1 or ‘The Onion’ Disappears Forever” read the headline, invoking a famous National Lampoon cover that threatened to shoot a dog if the magazine was not immediately purchased. (Lawson didn’t get the reference and was surprised when I mentioned it.) Beyond the recycled joke, the pitch had an odd resonance that spoke to the plight of digital journalism in general, whether fact-based or hilariously twisted. “You, the guileless reader, holding out hope against hope that The Onion will persist without your financial contribution,” it read, “you are the unreasonable one here.” That was no joke: Ultimately, we readers will get the journalism—or comedy—that we deserve. (If that makes sense to you, click here to subscribe to WIRED.)

Are people responding? Oh, yes. When I ask how much, Strle says, “Two billion.” Brillson corrects her. “Two hundred, 300 million probably,” she says. Look at them—Onion executives for a week, they’re already cracking jokes. “OK, all we can say is that it was really a nice amount of people,” says Strle. Some of them even gave more. “Not an insignificant number of people sent the maximum number of dollars, which I believe was 100 on the slider,” adds Brillson.

Those donations, of course, are only one of a number of business models that Global Tetrahedron will try out. Basically, Lawson’s team will reach into the grab bag of schemes that many sites have experimented with—subscriptions, commerce, premiums, merch. “We will have membership in various tiers,” says Strle. “We’ve been doing a lot of ideation with the staff about what kind of premiums we can offer, and what kind of experiences we can let people into.” Lawson says that he doesn’t envision a hard paywall. “However, we think we can actually make some new products, new experiences for our biggest fans that we think they will pay for.”

But the secret weapon for The Onion might well be the fact that Lawson doesn’t seem to aspire to media moguldom. He’s made his bundle in venture-backed Silicon Valley and doesn’t see The Onion as a way to a second fortune—and therefore is less likely to enshittify the outlet in the hunt for a big score. “During the digital boom there was a sentiment that you could get rich quickly off media,” says Brillson. “That is a really dangerous sentiment, especially when venture capitalism is involved. The truth is you can have a profitable media business, it just isn’t hockey sticking. Once you kind of realize, you know, you don’t need to triple revenue year over year, you can sustain a nice, upward trajectory.” (Of course, if Lawson is spotted at the Allen & Company Conference at Sun Valley in a Patagonia vest, all bets are off.)

One thing, however, looms over the revivification of The Onion. In its earlier days, its satire hit our funny bones by exaggerating the absurdities of our existences into unlikely lunacies. But in our current age, a former and potentially future president solidifies his voter base by going on trial for paying off a porn star. Two middle-aged deca-billionaires actually talked seriously about fighting an MMA cage match. A sizable percentage of AI scientists believe that there is a nontrivial chance that AI will wipe out humanity—and then spend their working hours accelerating its powers. How can satire thrive when actual reality is crazier?

Lawson isn’t daunted by that question. He thinks that our dumber century calls for even more satire. “Comedy is actually oftentimes people saying the things out loud that people are thinking,” he says. “When you express the truth, people look at around and say, like, ‘What the hell’s going on here?’” I hope he’s right, not just about the continuing value of satire, but to believe that entertaining content can thrive, and maybe even make a profit. I’m a journalist, and god knows I need something to laugh about, too.

Time Travel

WhatApp founders Jan Koum and Brian Acton were unhappy when Mark Zuckerberg removed the $1-a-year fee for the service and instead invoked an advertising and commerce-based business plan. That was only one of many indignities they suffered for the billions of dollars they reaped from being acquired by Facebook. Acton left the company in 2017, and Koum resigned a year later. “I just didn’t want to put ads in the product,” Acton later told me. I wrote about WhatsApp and its evolution in Facebook: The Inside Story.

The WhatsApp founders had firm views about their company’s business. They wanted to generate revenues early so they wouldn’t be beholden to funders. They lit on charging a monthly fee. “We were building a communication service,” says Acton. “You pay forty bucks a month to Verizon for their service. I figured a dollar a year was enough for a messaging service.”

Advertising, Acton would later say, “left a bad taste in my mouth.” As he came to see it, supporting a business with ads warped incentives, and led a company to create a suboptimal product for actual users. We’re whoring ourselves out!, he would rail at his boss at Yahoo. They had vowed that WhatsApp would never go down that wicked path. In 2011, Acton tweeted [a quote from the Fight Club movie]: “Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need.” In June 2012, they published a blog item laying out this philosophy.

When we sat down to start our own thing together three years ago we wanted to make something that wasn’t just another ad clearinghouse. We wanted to spend our time building a service people wanted to use because it worked and saved them money and made their lives better in a small way. We knew that we could charge people directly if we could do all those things. We knew we could do what most people aim to do every day: avoid ads.

“Remember,” they wrote. “When advertising is involved you the user are the product.”